Photo: Highwaystarz/Adobestock

Photo: Highwaystarz/Adobestock

Learning points

- Understand the role and significance of different forms of social media and technology in young people’s lives, identities and development, and their implications for wellbeing and safeguarding – both online and offline.

- How to use the “10 Cs” framework and approach to assessing online risks, harm and resilience from a child-centred perspective and as part of holistic assessments.

- Ways to better understand the experiences of young people and work in a relationship-based way with children and their families to help them enjoy the benefits of social media and digital technologies, while protecting them from online and offline risks.

Introduction

From everyday communication to education and homework, social media and digital technologies are an important part of children and young people’s lives and have a major influence on their relationships, identity and wellbeing. This offers great opportunities, but also new and significant risks and challenges for young people’s development and outcomes.

Gangs, criminal elements and other perpetrators of abuse have been quick to adopt new technology and exploit the curiosity and vulnerabilities of young people. In fact, social media and digital technologies play are important contributing factors and components of many safeguarding concerns, including sexting and cyberbullying, stalking, child sexual and criminal exploitation, county lines and more.

However, research indicates that practitioners do no routinely include detailed consideration of young people’s use of social media and digital technologies in assessments and safeguarding plans, except when concerns or referrals specifically relate to online risks (for example, cyberbullying). Even when children’s online lives are taken into account, most services do not have a child-centred model for assessing and managing online risks and their impact. This guide aims to help fill in this gap by providing an overview of an evidence-informed and systematic approach to assessing online risks and resilience, that can be integrated into routine assessments and direct work with young people and their families and carers.

Social media and young people’s identity

Note: the young people’s stories below are tragic examples of children who have taken their own lives. They are included to demonstrate the importance and impact of social media in children’s lives and relationships, and its implications for their development and wellbeing. Unfortunately, the stories of Tallulah and Ruby are not the only cases that highlight this.

Tallulah Wilson (2012)

Tallulah Mary Scarlett Wilson was 15 yearsold when she jumped in front of a train and killed herself. The coroner sent a Regulation 28: Prevention of Future Deaths Report (2014) to the health secretary; these are produced when the coroner believes the concerns raised indicate a risk of other similar deaths unless action is taken. The report said:

‘The jury found that, as a result of Tallulah’s dissatisfaction with her friendship group, she created an online persona. She posted about self-harm and suicide. She included photographs that she said were of herself following cutting.

Her consultant psychiatrist gave evidence that, with hindsight, it seems that when her Tumblr account was deleted (following her mother’s discovery of the damaging nature of her posts), Tallulah may have felt herself to be in some way deleted. Thousands of people had read her posts and she had gained great satisfaction from that. So, on the one hand, her internet use may have had a negative impact; and yet on the other hand, preventing her internet use may have had a negative impact.’

The jury included the following in the narrative determination:

“This case has highlighted the importance of online life for young people. We all have a responsibility to gain a better understanding of this, which needs to be achieved through appropriate dialogue. This is a particular challenge for health professionals and educators.”

The coroner then highlighted the key matter of concern:

‘Although Tallulah was treated by a number of healthcare professionals, and her mother was extremely concerned about her wellbeing, no person who gave evidence felt that, at the time they were looking after Tallulah, they had a good enough understanding of the evolving way that the internet is used by young people, most particularly in terms of the online life that is quite separate from, but sometimes seems to be used to try to validate, the rest of life.’

Ruby Seal (2017)

In spite of the powerful and important learning from Tallulah’s tragic death, many more young people have lost their life or experienced significant harm due to continued lack of understanding of online risks and appreciation for the experiences of young people. One such example is Ruby Seal. By the age of 12, Ruby Seal was self-harming due to low self-esteem and was referred to child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) for fortnightly visits. She also discovered Snapchat and in the words of her mum, Julie, “social media was like a drug to Ruby”. To “wean her off her addiction” her mum turned off the wifi and Ruby ran up a £200 mobile phone bill. In July 2016, Ruby was discharged by CAMHS. However, Ruby’s social media posts in the same year reflect a depressive mood with risk of self-harm and suicidal ideation and a strong desire for validation. (Her posts included ‘I might pop down to A&E and see if they can stitch my life back together’ and ‘How I sleep at night knowing I’m a disappointment and knowing no one cares about me’).

Ruby’s cries for friendship and desire for validation went unheard, and in the period leading to her death, her posts became increasingly disturbing. On 20 February 2017, Ruby posted two messages online, one saying “I think I might as well kill myself in the morning” and both remained unanswered. On 21 February, Ruby took her own life by hanging herself.

How can practitioners address online risk?

No social worker would complete an assessment without carefully considering the child’s experiences within the home and school environments as we know these have a great influence on children’s lives, development and wellbeing.

Children spend significant time online and considering the increasing evidence that online activities are one of the most frequent and significant sources of direct and indirect risks, it is essential that practitioners use motivational and relationship-based approaches to explore and understand the young people’s experiences online and assess online risks and resilience alongside other risks in their assessments and plans and as an integral part of safeguarding children and young people both online and offline.

How should we go about this? The relationship between the online world and our emotions and well-being are complex and multi-faceted.

However, technology and online experiences have a significant impact on young people’s identity, relationships and development and this can be both positive or negative. Therefore, the 10 Cs model considers online risk and digital resilience from a child-centred perspective and in relation to the child’s identity, relationships and development; hence, each of the 10 Cs considers both risks of negative outcomes and potential for positive outcomes and resilience online (by resilience we mean the person’s ability and resources to recover and overcome adversity and pursue his/her goals). The 10 Cs model and each of its risk and resilience categories are drawn from a systematic review of the existing literature on social media and safeguarding research, and a large scale multi-year research project involving practitioners, young people and their parents and carers. The 10 Cs model is set out in the Social Work England and PCFSW Best Practice Guide for Assessing Online Risks, Harm and Resilience and Safeguarding of Children and Young People Online. In this guide, we present the 10 Cs model, explaining and describing each risk and resilience category with examples and using a detailed case example (Alex’s story) to show how a practitioner could apply the model when assessing and working with a young person.

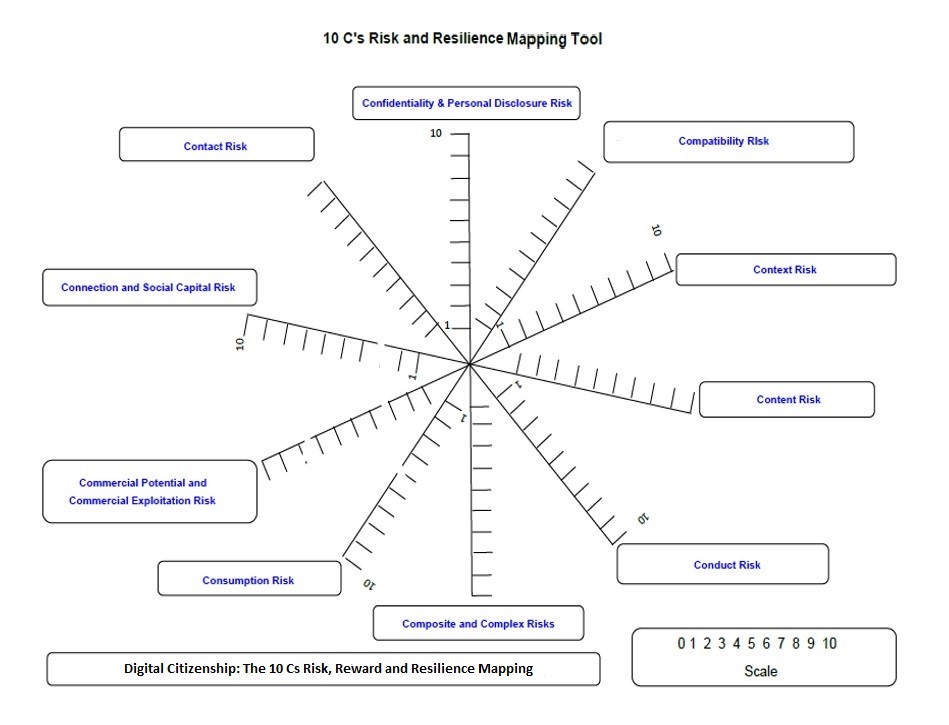

The 10 Cs are:

- Risks and resilience resulting from sharing or accessibility of personal information (confidentiality)

- Risks and resilience resulting from connections and social capital

- Risks and resilience resulting from the context of online activity (what platforms or apps are used)

- Risks and resilience resulting from content the young person is exposed to or creates

- Risks and resilience resulting from contact with others online or facilitated by technology

- Risks and resilience resulting from conduct online (the young person’s online behaviour)

- Risks and resilience resulting from compatibility (or lack of compatibility) between a young person’s offline and online identity, relationships, experiences and behaviour.

- Risks and resilience resulting from the child’s consumption (quantity, amount of time, frequency, pattern of use) of social media and technology

- Risks and resilience resulting from the commercial and professional potential of social media

- Complex risks and resilience resulting from the combination of multiple factors and risk areas

Use the links below to understand what each C involves and how to apply it in practice.

Using the 10 Cs in assessments and direct work

Practitioners can reflect with young people on each of the 10 Cs and explore the rewards or benefits and positives that they may derive in relation to each C from their online activities, identity and relationships. These positives could be scored from 0 to 10 where 0 represents the absence of any positive reward and 10 represents concrete and maximum positive reward or outcomes for the young person.

Similarly practitioners and young people can score from 0 to 10 the risks of harm or potential negative outcomes associated with the young person’s online activities in relation to each of the 10 Cs (where 0 represents no risk of harm or negatives and 10 represents actual harm or imminent risk of harm).

Reflectively scoring the positives and negatives of their online presence and activities with young people allows practitioners to gain an understanding of online risks and rewards from the young person’s perspective. This provides invaluable insight into young people’s life and significant opportunity for building on positives and safeguarding young people online. This mapping of risks and benefits will produce a child-centred visualisation of the young person’s risk and resilience profile based on their online identity and activities. The 10 Cs motivational approach creates a conversation that should lead to a shared understanding of risks and rewards and enable practitioners to generate shared goals to maximise the benefits and rewards while minimising the risk of harm for the young person with respect to each of the 10 Cs. For an example of using this tool with a young person, see Alex’s story.

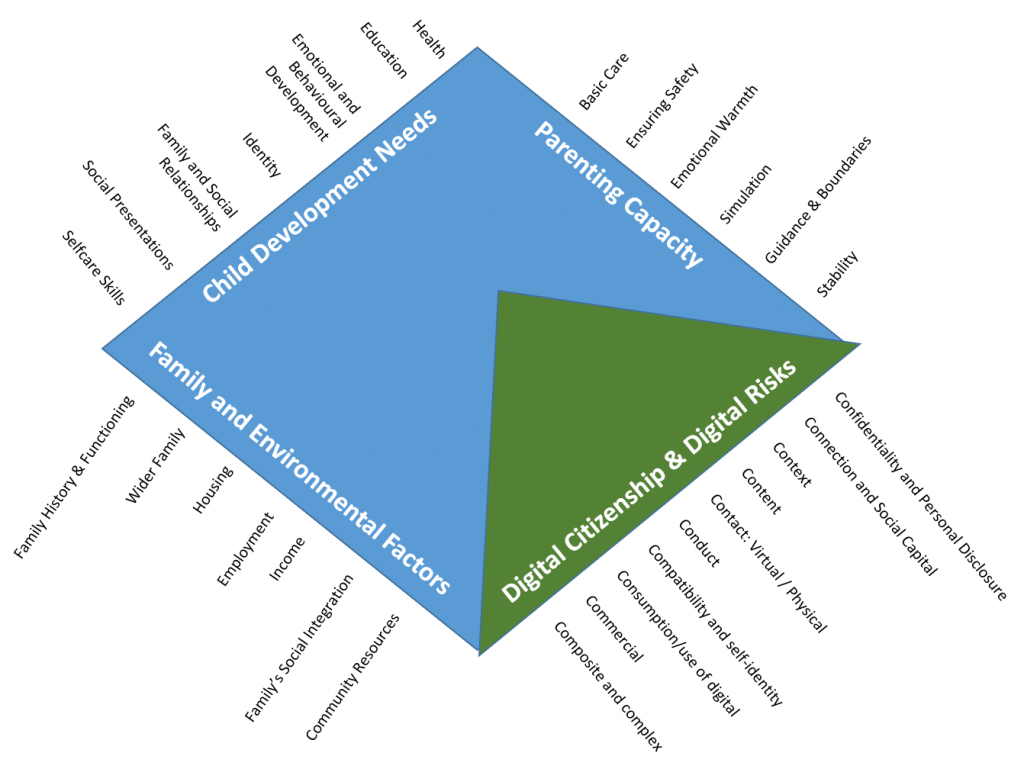

Working Together to Safeguard Children (2023) reinforces that “research has shown that taking a systematic approach to enquiries using a

Working Together to Safeguard Children (2023) reinforces that “research has shown that taking a systematic approach to enquiries using a

conceptual model is the best way to deliver a comprehensive assessment for all children.” The 2023 version of the statutory guidance continues to offer the familiar ‘assessment triangle’ of child’s developmental needs, parenting capacity and family and environmental factors as a key example of an assessment framework for a comprehensive and systematic assessment of needs and risks. Given the changing context of children and young people’s lives and the importance and impact of online activities and identities, we believe it is essential that assessment framework include the digital dimension of children and young people’s lives and their online experiences in the assessment framework.

Including the 10 Cs creates an ‘assessment diamond’ and offers a systematic approach for assessment of online and offline risks and holistic safeguarding of children and young people both online and offline (Buzzi, Megele and Blackmore, 2020 – see the Social Work England and PCFSW guide).

Conclusion

All social work practice and safeguarding should be a co-productive process, carried out in partnership with, and with active participation of, children and young people and their families and carers. Identifying and assessing online risks and safeguarding children and young people online is no different. A co-productive and motivational approach can be a crucial element of understanding their world, ensuring their voices and preferences are heard and respected, and gaining a better understanding of their perspectives, motivations, identity, relationships and behaviours.

Discussing and exploring the 10 C’s with a young person supports better safeguarding and a better relationship with a young person, while enhancing your understanding of their experiences. It is also empowering for young people, serving as a learning process for them to develop appropriate responses, actions and behaviours to mitigate online risks and enhance their resilience. It is therefore vital to assess the young person’s awareness and understanding of each of the 10 Cs to develop shared understanding and tailor our approach with a focus on the young person’s holistic wellbeing and based on their digital literacy.

The risk and resilience categories and their implications and ramifications also need to be considered within the child’s psycho-socio-ecological context and experiences as a ‘person-in-context’ (Adams and Marshall, 1996). This requires consideration of risks and resilience in relation to self, family and significant others, friends and peers, school, community and the wider environment and society, with sensitivity toward cultural and social norms and values.

The 10 Cs can also be used with parents and carers to increase their knowledge, understanding and appreciation of online risks and safeguard children and young people both online and offline.

These risk and resilience categories may or may not correspond to specific criminal or legal offences. However, from a safeguarding perspective, they offer a systematic understanding and structured approach to identification and assessment of online risks that can be integrated into current models of practice to provide a holistic approach to safeguarding. The 10 Cs can also be used for teaching and learning about risks and challenges and opportunities associated with social media and digital technologies.

Digital and social media technologies are rapidly transforming every aspect of society, practice and services. Future development will impact people’s use of social media and our relationship with technology as well as one another and this will pose new and complex risks and emerging opportunities. Therefore, it is essential that practitioners have a critical, child-centred and evidence-informed understanding of online risks, harm and resilience and are able to support and safeguard children and young people and their parents and carers in mitigating online risks and developing their online relationship, identity and resilience.

Effective safeguarding requires reflection and attentive observation of our environment and everyday experiences, can offer powerful insight and answers to complex questions. We have used the boat metaphor below to highlight the components of safety, stability and resilience and encapsulate the essence of effective safeguarding.

Think about a yacht (a 30, 40 or 50 metre yacht) in the middle of the sea; despite its size, powerful engine and all its safety features, a strong enough wind and wave can capsize and eventually sink the yacht. Now think about a small dinghy tied with a rope to a pole in a harbour. The waves and the wind might rock the boat or might lift the dinghy up in the air but the dinghy will fall back onto the water and continue to float and the same wave that capsized the yacht may overrun the dinghy but after it has passed, the dinghy will resiliently re-emerge and continue to float.

Before clicking in the box below, take a few minutes to reflect about what are the differences between the two boats and what is it that gives the dinghy such stability and resilience. What can we learn about safety, resilience and safeguarding from this observation?

The yacht and the dinghy – reflecting on safety, stability, resilience and effective safeguarding

Firstly, the yacht has a powerful engine and many protective measures and additional equipment for safety and comfort. However, those very features make the yacht heavier and once capsized, their presence and weight will eventually sink the yacht. This highlights the importance of context and that what may be considered a safety, well-being or protective measure in one context can be burden and harmful in another context. On the other hand, the dinghy is simple and not burdened by additional load and hence, resiliently remains afloat. This suggests we need to make safeguarding simple and support young people with a restorative and trauma-informed approach to lighten the burden of trauma they have observed and experienced in their lives.

Secondly, the dinghy is close to a harbour and the force of the winds and the waves usually diminish as they approach the harbour. This highlights that children and young people need a safe harbour to counter the force of adverse events in their lives. Also, the dinghy is tied to a pole and this stable connection prevents it from being carried away by the wave and being lost. Therefore, it is important that parents, carers and professionals offer a safe harbour and stable point of reference and the rope of validating and healthy relationships to ensure young people are well anchored that can prevent them from being carried away by other agents and life events or the waves and winds of adverse experiences.

Importantly, the rope offers the dinghy flexibility and this adds to its resilience. Indeed, if we replace the rope with a rigid wooden stick nailed to both the dinghy and the pole, chances are, soon the pole will break and the dinghy will be carried away and lost, even with light winds and waves. Therefore, it is important that we offer flexibility and room to play to enhance young people’s resilience and support them so they can experiment and explore, and learn and grow.

The metaphor of the dinghy and the yacht encapsulate the essence of effective safeguarding. If we offer young people a safe harbour and a point of reference and anchor them with the rope of positive and healthy relationships and allow them to play and explore at the highest level that they can positively and developmentally manage, we can watch them grow and blossom.

The 10 Cs offers ten relationship-based “ropes” to bond with and anchor young people, build professional relationships and connect with and understand their lives and experiences. More importantly, by learning about the 10 Cs, young people can develop their own compass and become better equipped to navigate and explore their ocean of experience.

Read more…

- Online safeguarding risks and resilience: using the 10 Cs in practice (Alex’s story)

- Learn on the go podcast: ethical and legal issues when considering service users’ social media

- Social networking and adoption

- Child development practice support tool

- Working with adolescents knowledge and practice hub

References

Adams GR and Marshall S (1996)

‘A developmental social psychology of identity: Understanding the person-in-context’

Journal of Adolescence, 19, 429-42

Buzzi P (2020)

National Research Project on Digital Practice, Digital Professionalism and Online Safeguarding (forthcoming)

Buzzi P and Megele C (2019)

Social Media and Social Work: Implications and Opportunities for Practice and Education

Bristol: Policy Press

Buzzi P, Megele C and Blackmore S (2020)

‘Social Work England and PCFSW Best Practice Guide for Assessing Online Risks, Harm and Resilience and Safeguarding of Children and Young People Online‘

The Principal Child and Family Social Worker Network and Social Work England

Billieux J, Philippot P, Schmid C, Maurage P, De Mol J, & Van der Linden M (2015)

‘Is dysfunctional use of the mobile phone a behavioural addiction? Confronting symptom-based versus process-based approaches’

Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(5), 460-468

Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) (2016)

‘Child Safety Online: A Practical Guide for Providers of Social Media and Interactive Services’ Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport and Baroness Shields OBE

Emerson, RM (1976)

‘Social Exchange Theory’

Annual Review of Sociology (2) 335-362

Erickson E (1968)

Identity, youth, and crisis

London: WW Norton

Gámez-Guadix M, Orue I, Smith P and Calvete, E (2013)

‘Longitudinal and reciprocal relations of cyberbullying with depression, substance use, and problematic internet use among adolescents’

Journal of Adolescent Health, 53 (4), 446-452

Kleck C, Reese C, Sundar SS (2007)

The company you keep and the image you project: putting your best face forward in online social networks

Paper presented at 57th Annual Conference of the International Communications Association, San Francisco CA.

Laurenceau, J, Barrett L and Pietromonaco P (1998)

‘Intimacy as an Interpersonal Process: the Importance of Self-Disclosure, Partner Disclosure, and Perceived Partner Responsiveness in Interpersonal Exchanges’

Journal of personality and social psychology. 74, 1238-51

Luhmann N (1984)

Social Systems

Stanford CA: Stanford University Press

McLuhan M (1964)

Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man

Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press

Megele C and Buzzi P, (2017)

Safeguarding Children and Young People Online

Bristol: Policy Press

Mehdizadeh S (2010)

‘Self-Presentation 2.0: Narcissism and Self-Esteem on Facebook’

Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 13(4), 357-364

Karakurt G and Silver KE (2014)

‘Therapy for childhood sexual abuse survivors using attachment and family systems theory orientations’

The American Journal of Family Therapy 42 (1), 79-91

Suler, J (2004)

‘The Online Disinhibition Effect’

Cyberpsychology & behavior : the impact of the Internet, multimedia and virtual reality on behavior and society. 7, 321-6.

Tan X, Qin L, Kim Y & Hsu J (2012)

‘Impact of Privacy Concern in Social Networking Websites‘

Internet Research. 22(2) 211-233

Tong ST, Van Der Heide B, Langwell L and Walther JB (2008)

‘Too Much of a Good Thing? The Relationship between Number of Friends and Interpersonal Impressions on Facebook’

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(3), 531–549

De Vito JA (1986)

The communication handbook

New York: Harper & Row

Wheeless, LR, & Grotz J (1976)

‘Conceptualization and measurement of reported self-disclosure’

Human Communication Research, 2(4), 338–346

Winnicott DW (1975)

‘Transitional objects and transititional pehnomena’, in Through paediatrics to psychoianalysis

London: Hogarth Press.

Worthy M, Gary AL, Kahn GM (1969)

‘Self-Disclosure as an Exchange Process’

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13(1), 59–63

Zywica and Danowski (2008)

‘The Faces of Facebookers: Investigating Social Enhancement and Social Compensation Hypotheses; Predicting Facebook™ and Offline Popularity from Sociability and Self‐Esteem, and Mapping the Meanings of Popularity with Semantic Networks’

Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication. 14. 1 – 34. 10

Knowledge and Practice Hubs

Knowledge and Practice Hubs